.webp)

Like its seven cousins, dance is a noble art that carries deeper meanings. Far from being a simple form of entertainment or a mere recreational activity, it is seen as a medium to preserve memory and foster identity. Recorded history shows us that movement has been humanity’s privileged way to observe rituals, mark festivities, celebrate reinvention, and ultimately, narrate our stories.

Regardless of the historical setting, dance has been used to codify life. In ancient times, great polities used it to venerate gods, celebrate seasonal changes, honor fertility, and define social affiliation. Therefore, imagine how Lebanon, which has been subjugated to numerous empires, must have been impacted. Phoenician coastal rituals, Mesopotamian temple choreographies, Arab court traditions, Islamic aesthetics, and Ottoman rule, left their imprint on the land of the cedars and its intangible culture.

During the Phoenician era, dancers performed in temple courtyards along the coastal cities during rituals dedicated to their main deities, such as Astarte, Baal and Melqart. Dressed in flowing linen robes and layered bronze jewelry, their movements invoked fertility, maritime protection, and seasonal renewal. Mesopotamia, the great regional powerhouse, gave religious dance an even more structured role within temple liturgy. For instance, the priestesses of Inanna and Ishtar performed sacred choreographies during New Year festivals and victory celebrations.

Several centuries later, Lebanon came under Islamic rule and influence. In the early days of Islam, some conservative scholars casted a negative light on dance, associating it with frivolity or seduction. Other schools of thought, like Sufism, conferred it a profound spiritual legitimacy. They saw in rhythm and rotation a pathway to divine ecstasy. Under Ottoman rule, a duality emerged. The imperial court developed a rather distinctive aesthetic influenced by Persian, Anatolian, and Arab influences. For example, male and female dancers performed refined and elaborated pieces accompanied by an assortment of oud, qanun, and percussion instruments. On the other hand, folk dances which existed for centuries, like dabkeh, continued to thrive in villages and towns, especially during communal festivities and weddings.

As improbable as it may seem, dabkeh is more than one thousand years old! Its roots can be traced back to the ancient Levantine building and harvest rituals, where villagers held hands and stomped in unison to pack the mud on rooftops. This practice was called al-awneh, a word of Aramaic origins that means “let’s go and help”. There is also “el houwara”, a dabkeh dance style characterized by its high tempo, intensive footwork, and showmanship. Between the 1930s and 1960s, it gained incredible traction and was widely popularized by the Rahbani theater and Baalbek’s festivals.

One of the stars of Baalbek was Sabah, whose folkloric numbers and choreographies that gave this dance a second golden age at the regional level. Simultaneously, Abdel-Halim Caracalla harnessed dabkeh’s scenography potential to the fullest extent, which allowed for the genre to be promoted internationally. A generation later, Fady Lebnen pushed it into the modern age. By putting emphasis on spectacular moves, he embodied a new masculine heroism on stage.

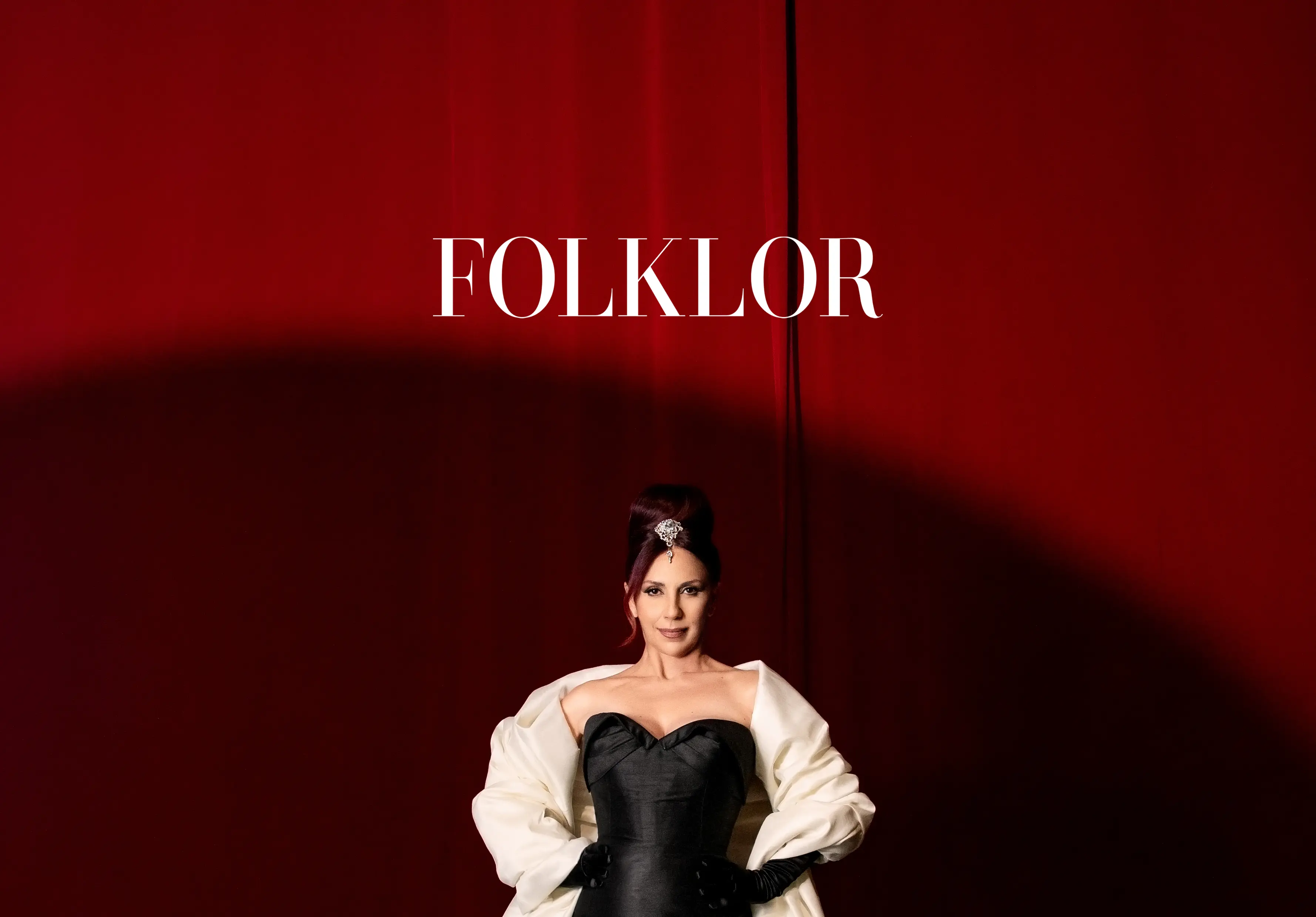

In the meantime, a talented female artist was about to become the sweetheart of the nation. Confident, powerful, culturally rooted, and modern, the iconic Amani was on the rise. Her grace merged classical Arab sensuality with theatrical sophistication. Her performances were meticulously choreographed and accompanied by live orchestras. By reframing the public perception, she managed to rehabilitate belly dancing, remove the “nightclub spectacle” label, and walk in the footsteps of her worthy predecessor Nadia Gamal.

Fast forward to 2005 and the Lebanese cinema was still obsessed with the Lebanese Civil War. Directors and writers were trying to find answers to unanswered questions, fifteen years after the guns fell silent. Like his peers, Phillipe Aractingi embarked on this journey and gave us “Bosta” (the bus), a movie that (un)consciously captured the essence of millennial Lebanese pop culture. Putting dabkeh, of all things, right, front and center to tackle this sensitive issue seemed an odd choice at first glance, but proved to be a masterstroke. The very eclectic and diverse dance crew that toured Lebanon in their red “bosta” were an allegory of the country. They represented a new generation that wanted to shape the future of their homeland. The highly symbolic face-off between the old men of Baalbeck in their traditional sherwel dancing to the tunes of traditional songs and the young crew in their colorful, flashy, neon streetwear jumping to the beats of electro-dabkeh transcends the traditional generational clash. This scene showcases that heritage can be reinvented, be a unifying force, and guide a nation forward while remaining true to its roots.

In 2007, the revival continued with the TV belly dancing competition “Hizzi Ya Nawaem”. At a time when social media was still in its infancy, it was difficult to comprehend why the show took on an international dimension by including participants from distant lands, like Brazil and Russia. Almost two decades later, it is possible to review this production with the power of hindsight. Designed for domestic entertainment, it opened the doors for the whole world to see what modern Arab dancing could be, where it gets its influences, and where traditional Levantine or Lebanese dance moves fit within that frame.

Then the hype faded away and the genre entered a long decline, until it was revived during the pandemic. Stuck in their homes, many started to dance in their living rooms and share the footage on social media, especially Tiktok. Lone individuals turned into zaffeh groups in high demand. Although their outfits don’t accurately reflect our heritage, their impact was tangible nonetheless. As I am writing this, MTV is promoting a new show called “Let’s Dabke” … so, yalla, a’l seha and let us celebrate a vibrant story that is in constant renewal and profoundly authentic.